Design Operations Guide

Analyzing Designs

Click to enlarge the above image

Convergent Thinking

The frameworks in this section will help you take apart your prototype(s) in an analytical way, design tests for the prototype(s), and then evaluate the results of those tests. This phase is as close to the Scientific Method that the design process gets. It can very fun!

The purpose of this section is to start to understand how your prototypes perform in the real world with real participants.

Analyzing Designs

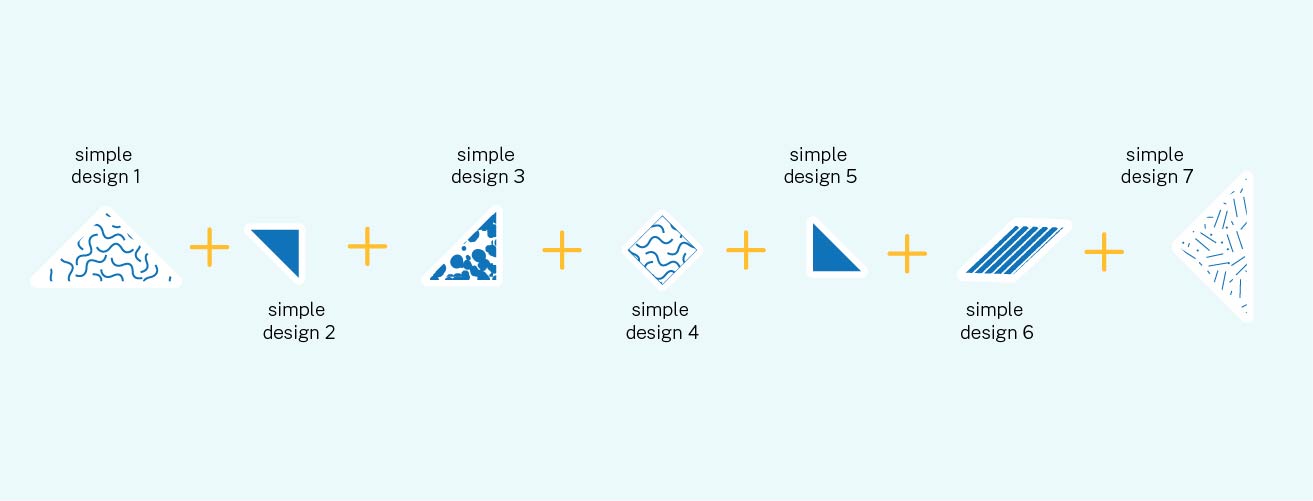

Through this section, you’ll understand if you’ve made a simple, complicated, or complex idea. Some brief definitions of these are:

-

Simple: A simple design is one that can stand alone, without core dependencies on any other product, service, or system that will make or break its success. A fan is an example of a simple design.

-

Complicated: A complicated design is one that has many parts that all have to work in unison for the designed thing to function. A common example of a complicated design is an engine. It has many parts, including the fan from the simple example above, but the parts are easily ennumerated, can be replicated, and can be fit together according to a set of instructions.

-

Complex: A complex design is one in which many, sometimes competing, sometimes themselves complex, items come together. An example of this is the airline industry, which in order to function has to bring together the engines from the above example, the business of running airlines, the policy worlds of safety and environmental regulations, of labor relationships, of geopolitics, of market demand, and of many other intricate systems.

Understanding Complexity

Use the framework in this section to analyze the design or designs that the team has decided to forward and test different expressions of their parts. Through the earlier processes of divergent thinking in idea generation and convergent thinking in constraints and skills mapping and references gathering, the shape of your design creation has emerged. Break that shape down into its component parts to determine how to start the making process.

Complex Designs

To review the definition from the introduction to this section, a complex design is one in which many, sometimes competing, sometimes themselves complex, items come together.

An example of this is the airline industry, which in order to function has to bring together the engines from the above example, the business of running airlines, the policy worlds of safety and environmental regulations, of labor relationships, of geopolitics, of market demand, and of many other intricate systems.

If you break down your design and find that, in fact, you have proposed something that is complex, not to worry. However, please do return to the Setting Up phase, take a good, hard look at your Opportunities, resources, and design principles, and center on developing a less-involved design idea.

A complex product is, by nature, a tenious design. Even if you can realize it, its own complexity renders it brittle and prone to breakage. Most of the time, however, these designs are not even realizable because they depend on too many disperate factors to all come together. Please do not attempt to design a complex product, service, or system unless you have years of lede time, deep, cross-institutional buy-in, sit at a very high level, strategy position in your organization, and have a reasonable belief that you will occupy that position for years to come. Even if you believe you have leadership buy-in, unless you are the leader, we would not advise this course.

Complicated Designs

If you break down your design and find that you’ve proposed a complicated design, that’s okay. However, it will have implications for your timeline.

In a complicated design, you and the team will need to identify all the parts of the design, isolate them, create different expressions or prototypes of them, test the prototypes, bring the parts together in an intentional, rational sequence and test each time you add a part, then finally test the design as a whole. It is a do-able process; however, it can be quite lengthy.

In addition, be aware that complicated designs are brittle. With so many parts comprising them, they tend to break over time. Be aware of maintenance requirements if you decide to design a complicated product, service, or system.

Simple Designs

The authors of this Guide recommend that you attempt to create simple designs, deployed sequentially across time in order to create an agile ecosystem of products, services, and systems that can act in concert and flex around changing circumstances.

There is power in simplicity, and power in a series of simple designs, well-executed, acting in concert.

If you create a series of simple designs that answer participant needs, with time it is possible to serve your most complex design principles and achieve high-level strategic goals. As the global design principles in the Design Concept Guide state, though, Getting to Simple is Hard. A simple design is not always one that is obvious: it is focused and flexible. Focused because it answers participant needs; flexible because it can function as context and usage changes over time.

Framework - Analyze Your Designs

Use the framework below to start analyzing the design concepts you and the team have come up with. Descibe your design in as much detail as possible. When it gets hard, push through. This the time to work out the tough parts that you’ve perhaps been avoiding laying out up until now. Print out more pages or just draw the framework on blank sheets if you need more space.